Wes Anderson é um gosto adquirido. Entendo quem não aprecie a sua obra, apoiado no argumento de que é estilo, e não substância, ou de que a forma milimetricamente precisa sufoca a emoção que poderia surgir dos temas sensíveis e relações familiares em que investe. É a aparência de casa de bonecas, a composição simétrica, ao menos bastante organizada, ou as atuações desnaturalizadas, com ritmo e cadência próprias, dentre outros recursos, que fazem o seu cinema ser o que é, atribuem uma assinatura em uma arte cada vez mais uniformizada e pasteurizada. Ainda bem que há cineastas iguais a Wes que, mesmo em filmes medíocres como O Esquema Fenício, sobressaem-se da média do cinema contemporâneo.

Ao lado do colaborador habitual Roman Coppola, Wes conta a trajetória de Zsa-Zsa Korda (Benício Del Toro, que retoma a parceira com o diretor após o ótimo Conexão Francesa), um magnata e empreendedor alvo de tentativas de assassinato que falham em levar a termo o seu intento. A mais recente acarretou a sua ida ao julgamento no céu, até despertar e tomar a decisão de reatar o relacionamento com a filha, a noviça Leisl (Mia Threapleton), elaborando o plano para levar adiante o esquema do título - que envolve a participação de investidores ao redor do mundo - e convencer a filha a abandonar os votos e aceitar ser a sua herdeira. Ela aceita, desde que possa vingar-se da pessoa que provocou a morte da mãe, o tio Nubar (Benedict Cumberbatch).

Emocionalmente, O Esquema Fenício requenta o tema apresentado em Os Excêntricos Tenenbaums, em que uma figura patriarcal decide reconstruir o relacionamento com sua família. Com o passar do tempo, Zsa-Zsa e Liesl encontram o ponto em comum, um em que a ex-noviça pode investir no voto de pobreza, mesmo quando a ganância do pai fala mais alto, ao presenteá-la com peças elaboradoras do que ama (por ex., o cachimbo cravejado em joias). No entanto, diferente de obras anteriores, nas quais a estrutura narrativa era aninhada, com o texto dentro do texto (às vezes dentro de um outro texto, por ex. o trabalho passado Asteroid City), este roteiro é linear, mesmo que empregue um formato gamificado, com suas fases delimitadas em ‘caixas de sapato’ e no plano de convencer os investidores originais a aumentar a sua participação após o preço das commodities ter disparado e ser necessário o preenchimento da lacuna.

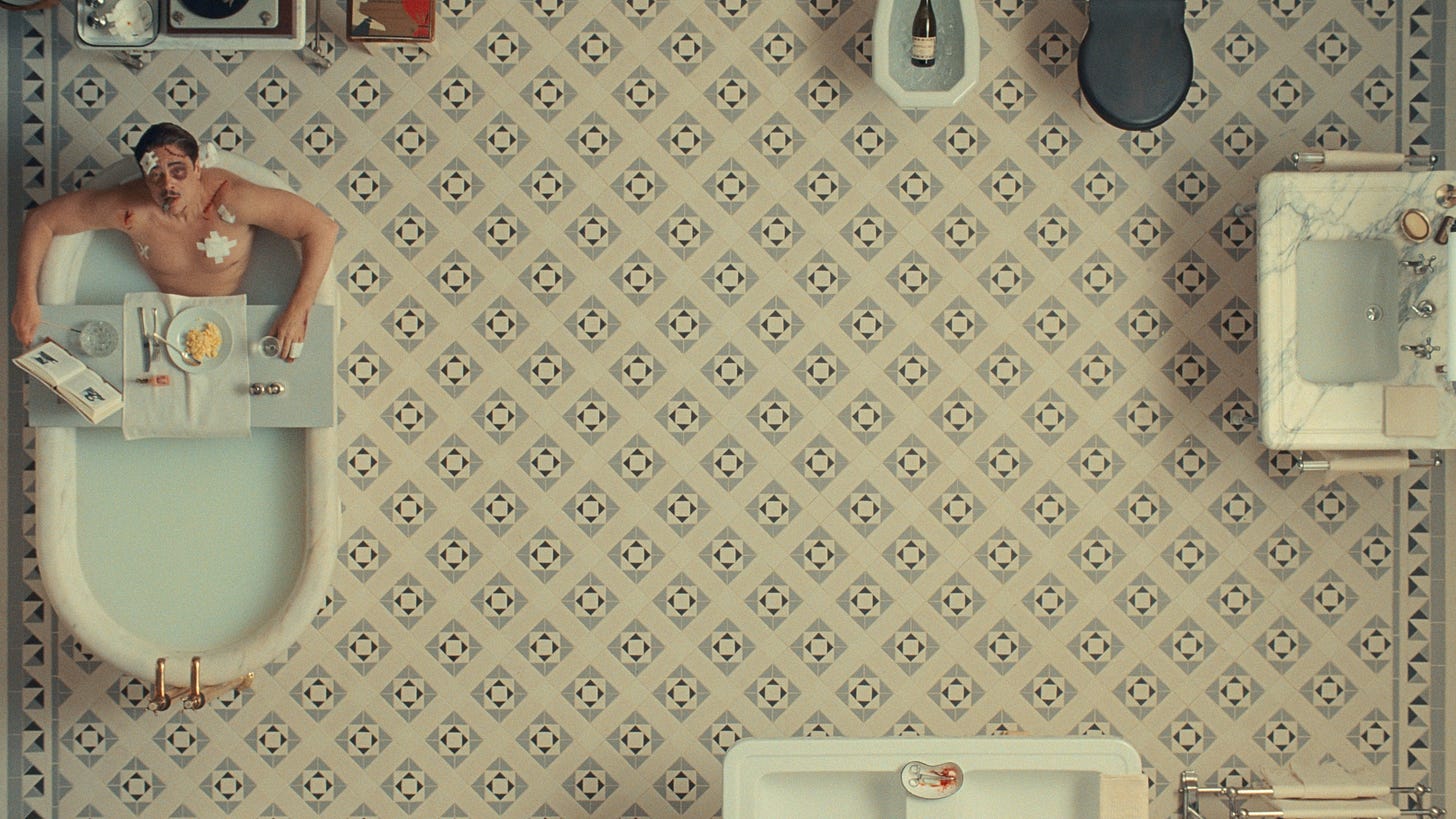

A estrutura é acomodada e acomoda a trupe do diretor, que só cresce: Riz Ahmed ou Michael Cera estreiam no cinema do autor, que convidou de novo Tom Hanks, Bryan Cranston, Scarlett Johansson e Jeffrey Wright (uma dúzia mais). O prazer existe neste reencontro com rostos conhecidos, dobrando-se à visão idiossincrática do autor, até quando os momentos individuais proporcionam menos do que poderiam resultar em se tratando do elenco à disposição. Mesmo assim, há prazeres relativamente inéditos considerando o cinema do autor: se você já refletiu ‘e se Wes dirigisse Top Gun ou até Missão: Impossível’, a narrativa oferece a chance de assistir à explosão de um avião, ou as suas consequências violentas, e mesmo uma sequência de artes marciais. O diretor até inventa o que denominei de slap shot, quando uma personagem estapeia o rosto de outro e a câmera ao mesmo tempo.

Mas eu sinto falta mesmo de momentos em que toda essa arquitetura, que hipnotiza o olhar de tal maneira que queremos apreciar cada objeto, textura ou figurino, converge em uma emoção genuína, por mais que seja pontual. Liesl pondera que, quando reza a Deus, não tem resposta, então somente realiza o que Deus acharia melhor. É até óbvia a conclusão, mas uma verdade adequada à emoção buscada na narrativa, pois não seria o hábito ou os votos que fariam de Liesl uma esposa de Deus, mas a sua bondade. Este é um momento raro, em que a atuação distanciada de Mia não subtrai a personalidade de sua personagem. Já o senso de humor é melhor, com tiradas irreverentes acentuadas pela atuação eficiente de Benício Del Toro, ou do restante do elenco.

Pessoalmente, acredito que seja incapaz de desgostar da obra de Wes: depois de haver compreendido que o diretor exerce o controle na precisão formal como meio de domar temáticas complexas (não é incomum que sua obra trate de trauma, luto, suicídio, aqui de abandono), eu me sinto capaz de enxergar além da beleza estética para o interior de personagens que escondem de nós os seus sentimentos, porque teme tê-los frustrados. O Esquema Fenício não muda essa realidade. Eu adorarei revê-lo mesmo assim, quando estrear nos cinemas.

English review

Wes Anderson is an acquired taste. I understand those who don't appreciate his work, arguing that it's style, not substance, or that the meticulously precise form stifles the emotion that could emerge from the sensitive themes and family relationships he invests in. It's the dollhouse appearance, the symmetrical composition, at least quite organized, or the denaturalized performances, with their own rhythm and cadence, among other resources, that make his films what they are, and give them a signature in an art form that is increasingly uniform and pasteurized. Thank goodness there are filmmakers like Wes who, even in mediocre films like The Phoenician Scheme, stand out from the average of contemporary cinema.

Alongside his regular collaborator Roman Coppola, Wes tells the story of Zsa-Zsa Korda (Benício Del Toro, who renews his partnership with the director after the excellent The French Connection), a tycoon and entrepreneur who is the target of assassination attempts that fail to carry out their intent. The most recent one led to her going to judgment in heaven, until she awakens and decides to rekindle her relationship with her daughter, the novice Leisl (Mia Threapleton), devising a plan to carry out the title scheme - which involves the participation of investors from around the world - and convince her daughter to abandon her vows and accept being her heir. She accepts, as long as she can avenge the person who caused her mother's death, Uncle Nubar (Benedict Cumberbatch).

Emotionally, The Phoenician Scheme reheats the theme presented in The Royal Tenenbaums, in which a patriarchal figure decides to rebuild the relationship with his family. Over time, Zsa-Zsa and Liesl find common ground, one in which the former novice can commit to the vow of poverty, even when her father's greed speaks louder, by giving her elaborate pieces of what he loves (e.g., the bejeweled pipe). However, unlike previous works, in which the narrative structure was nested, with the text within the text (sometimes within another text, for example, the previous work Asteroid City), this script is linear, even if it uses a gamified format, with its phases delimited in ‘shoe boxes’ and the plan to convince the original investors to increase their participation after the price of commodities has soared and it is necessary to fill the gap.

The structure is accommodating and accommodates the director's troupe, which is only growing: Riz Ahmed and Michael Cera make their film debuts with the author, who has once again invited Tom Hanks, Bryan Cranston, Scarlett Johansson and Jeffrey Wright (a dozen more). There is pleasure in this reunion with familiar faces, bending to the author's idiosyncratic vision, even when the individual moments provide less than they could have if the cast were available. Even so, there are relatively new pleasures considering the author's cinema: if you've ever thought 'what if Wes directed Top Gun or even Mission: Impossible', the narrative offers the chance to watch a plane explode, or its violent consequences, and even a martial arts sequence. The director even invents what I called a slap shot, when a character slaps another character in the face and the camera at the same time.

But I really miss moments when all this architecture, which hypnotizes the eye in such a way that we want to appreciate each object, texture or costume, converges in a genuine emotion, however punctual it may be. Liesl ponders that, when she prays to God, she gets no answer, so she only does what God would think best. The conclusion is even obvious, but a truth appropriate to the emotion sought in the narrative, because it would not be the habit or the vows that would make Liesl a wife of God, but his kindness. This is a rare moment when Mia's detached performance doesn't detract from her character's personality. Her sense of humor is better, with irreverent quips accentuated by the efficient performance of Benicio Del Toro, or the rest of the cast.

Personally, I believe I'm incapable of disliking Wes's work: after understanding that the director exercises control in formal precision as a means of taming complex themes (it's not uncommon for his work to deal with trauma, grief, suicide, and here abandonment), I feel able to see beyond the aesthetic beauty to the interior of characters who hide their feelings from us because they fear having them frustrated. The Phoenician Scheme doesn't change this reality. I'll love to see it again anyway, when it opens in theaters.