No livro New Hollywood Cinema: An Introduction, Geoff King reflete que há, hoje em dia, uma instabilidade entre as fronteiras dos gêneros cinematográficos comparado com o que havia no período clássico. Geoff exemplifica com Um Drink no Inferno, de Robert Rodriguez, que vem imediatamente à cabeça quando penso em Pecadores. E não é apenas porque ambos exploram o horror vampírico, e as convenções atreladas, mas sobretudo em como, estruturalmente, ambos os filmes renegociam os termos de nossa experiência no meio do caminho, transformando-se como homens em vampiros, ou como o negro recém emancipado em contato com o branco que antes o escravizou e agora pretende se apropriar do que lhe é caro: a ancestralidade, o espírito e a arte.

Fotografado em película de 70mm, com uma razão de aspecto adaptável, dependendo da atmosfera e do estado emocional da narrativa, Pecadores ambienta-se na década de 30, quando os gêmeos Fumaça e Fuligem (Michael B. Jordan) retornam endinheirados de Chicago, onde trabalhavam como capangas de Al Capone, com o plano ambicioso de transformar o armazém onde eram açoitados, torturados e assassinados negros por escravagistas em um ambiente para que os trabalhadores das plantações de algodão e ex-escravizados pudessem confraternizar, beber, dançar e ser quem nasceram para ser. Não que Fumaça e Fuligem sejam santos - são gângsteres -, já que o capitalismo rege as suas ações, mas a decisão de construir um empreendimento devolva parte aos seus e àquela região marginalizada e aterrorizada com a violência jamais finda do Klu Klux Klan, além de tensionar a balança do poder naquela região.

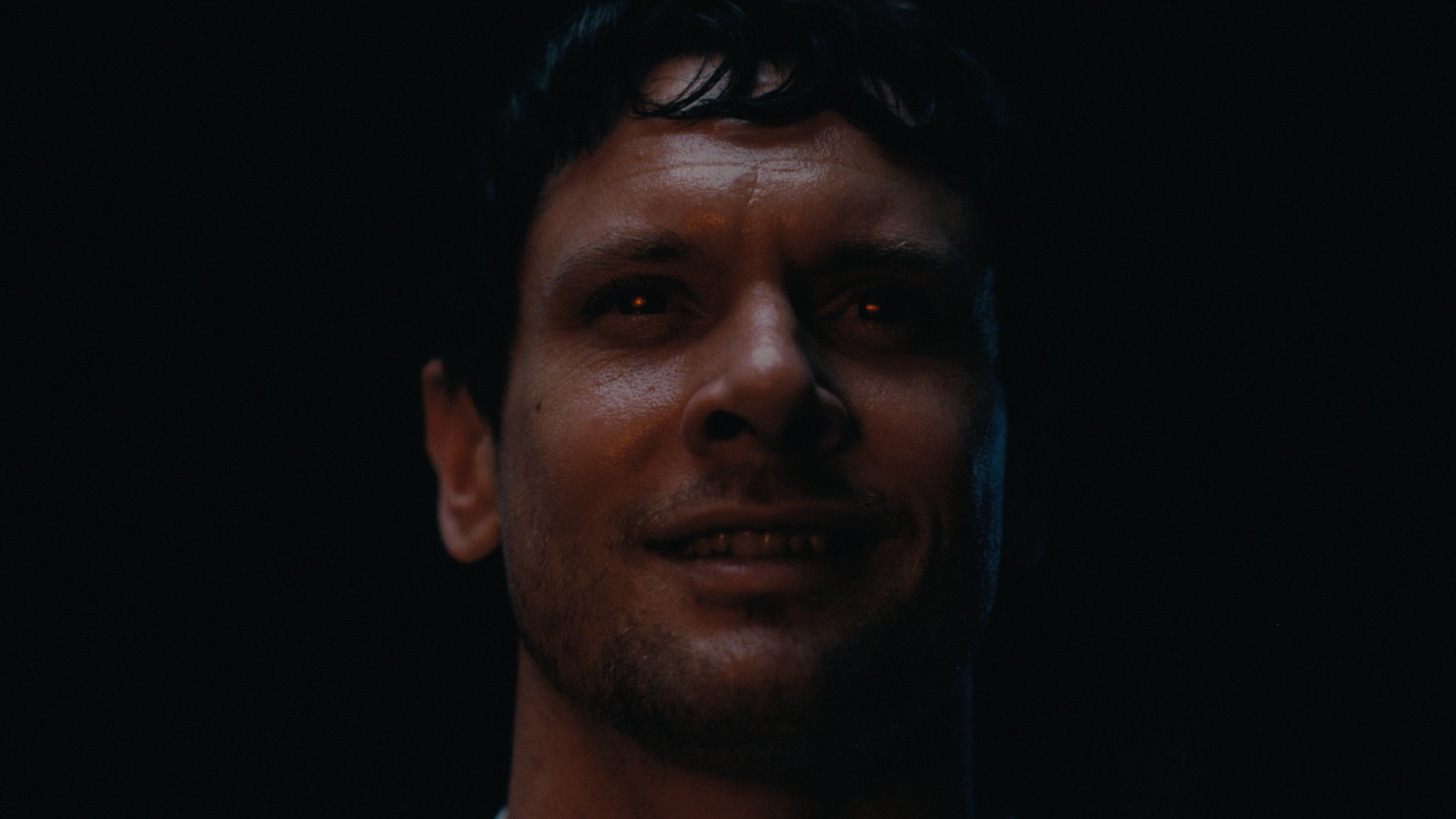

Durante a metade inicial de Pecadores, Fumaça e Fuligem dividem-se para comprar os comes e contratar os músicos. Sammie (Miles Caton), o primo dos gêmeos e o filho do pastor local, acompanha-os com uma guitarra de prata herdada do tio. Ele é quem tem o poder de, com a música, transcender a barreira do tempo, reunir passado, presente e futuro em um ato de estupor e suspensão do momento, convidar os ancestrais e o mal, na figura do vampiro irlandês Remmick (Jack O’Connell). É uma sequência que jamais esquecerei. A técnica é exuberante: a câmera está enfeitiçada pela vozeirão de Miles, e pelo ritmo e dança de corpos, e é como se perdêssemos, nem que temporariamente, as faculdades do corpo mediado pelo aparato cinematográfico. Mas não é a técnica, e sim a alma. A apoteose de Pecadores é agregadora, ainda que tal agremiação esteja limitada ao coro presente. O hip hop, o balé clássico, a guitarra de Jimi Hendrix e a cantoria de celebrações africanas encontra a ancestralidade chinesa, não há mais barreiras, só há corpos que se movem à sua forma, no seu tempo, apenas se mexem. Mexer-se é bom, é sinônimo de progresso.

O melhor é perceber que não há maniqueísmo no retrato de Ryan Coogler: Remmick parece propor o mesmo, mas por caminho diferente. Ao invés da libertação da alma e do convite a confraternizar com quem fomos e quem seremos, Remmick defende uma forma de assimilação, e toda assimilação exige que abramos mão de quem somos. Ele entoa um canto folclórico, que é igualmente hipnótico quanto o que é entoado no bar, e todos os corpos mortos-vivos dançam e cantam a mesma harmonia de Remmick. É a perda do eu para ser aceito entre diferentes, para ter o poder de derrotar o ódio racial. Pecadores utiliza a sua narrativa ambiciosa para discutir se desejamos renunciar quem somos em favor da aceitação pela via da assimilação, que sempre é falsa, pois devora e destrói a alma. Sua metáfora vampírica (com toda a parafernália de estaca de madeira, água benta, alho etc.) interroga a comunidade afro-americana, mas pode ser qualquer grupo minoritário, se vale a pena aceitar a ameaça dos colonizadores que promovem o ódio e a violência. Eu posso imaginar, apesar de meu olhar limitado, o filme como um diálogo com a mulher negra que alisa o cabelo crespo para ser aceita dentro do padrão estético branco, ou do homem que nega vestes tradicionais, ou do artista que fotografa a pele negra como se esta tivesse as mesmas propriedades da pele branca, de absorção, reflexividade e beleza.

Na sociedade conformista, cantar o blues e dançar o ritmo dos ancestrais é um pecado. E adoro o fato de que Coogler reconhece a apatia do grupo reduzido de sobreviventes, que pretende salvar-se esperando o nascer do sol, como se esse fosse uma promessa de um amanhã melhor, não só a antecipação da noite, na qual ódio e violência prometem repetir-se. A forma de enfrentar o mal é combatê-lo, não se recolher nos bares e guetos para onde a sociedade empurra esses grupos marginalizados, e quem convida o mal é a chinesa Grace (Li Jun Li), que é quem ‘dirige’ a movimentação da câmera em instantes específicos. Sem querer, Pecadores dialoga com o agora na retaliação chinesa contra os atos imperialistas estadunidenses. É um acaso, sim, mas que funciona na narrativa. Eu até poderia queixar-me do confronto, pela sua brevidade e pelo seu descompasso - por que parece haver mais humanos do que vampiros, será que os ancestrais retornaram a fim de ajudar? -, mas eu estaria jogando palavras fora. Meu papel como crítico não é o de apontar ‘acertos’ e ‘erros’, mas o de proporcionar, a meu leitor, a experiência através de meu olhar.

O clímax só incomodou o meu-eu racional, porque a minha alma desejava aprender os passos de dança e respeitar o ritmo sempre oscilante do blues, e depois combater junto àqueles ameaçados de perder a raiz que os une à sua ancestralidade e espiritualidade. A alma de Pecadores é belíssima, e os melhores filmes são imperfeitos mesmo, porque quanto mais autêntica a arte, maior o risco de frustrar fórmulas e convenções em prol do agora. Ryan Coogler, você me tirou do eixo, mas eu ofereço minhas palavras finais a Wunmi Mosaku, por cuja atuação eu já me encantei no terror sobre xenofobia O Que Ficou Para Trás (2020) e por que agora me apaixonei de vez, e Delroy Lindo, que é quem melhor retrata, por sua maturidade e sensibilidade os temas traumáticos de Pecadores, enquanto sua jovialidade e senso de humor moleque reforçam os elementos típicos do gênero, já que, no fim, fazer um filme de gênero é um piscar de olhos ao espectador.

Ou um riff de guitarra sobrenatural.

English review

In his book New Hollywood Cinema: An Introduction, Geoff King reflects that there is, nowadays, an instability between the boundaries of cinematic genres compared to what existed in the classical period. Geoff exemplifies this with From Dusk Till Dawn, by Robert Rodriguez, which immediately comes to mind when I think of Sinners. And it is not only because both explore vampire horror, and the conventions attached to it, but above all because, structurally, both films renegotiate the terms of our experience along the way, transforming themselves like men into vampires, or like the newly emancipated black man in contact with the white man who previously enslaved him and now intends to appropriate what is dear to him: his ancestry, his spirit and his art.

Shot on 70mm film, with an adaptable aspect ratio, depending on the atmosphere and emotional state of the narrative, Sinners is set in the 1930s, when the twins Smoke and Stack (Michael B. Jordan) return wealthy from Chicago, where they worked as Al Capone's henchmen, with the ambitious plan of transforming the warehouse where black slaves were whipped, tortured and murdered into an environment where cotton plantation workers and former slaves could socialize, drink, dance and be who they were born to be. Not that Smoke and Stack are saints - they are gangsters after all! -, since capitalism governs their actions, but the decision to build a business gives something back to their own people and to that region marginalized and terrorized by the never-ending violence of the Klu Klux Klan, in addition to straining the balance of power in that region.

During the first half of Sinners, Smoke and Stack split up to buy food and hire musicians. Sammie (Miles Caton), the twins’ cousin and the son of the local pastor, accompanies them with a silver guitar inherited from his uncle. He is the one who has the power to transcend the barrier of time with music, to bring together past, present and future in an act of stupor and suspension of the moment, to invite the ancestors and evil, in the figure of the Irish vampire Remmick (Jack O’Connell). It is a sequence that I will never forget. The technique is exuberant: the camera is enchanted by Miles’s booming voice, and by the rhythm and dance of bodies, and it is as if we lose, even temporarily, the faculties of the body mediated by the cinematic apparatus. But it is not the technique, it is the soul. The apotheosis of Sinners is unifying, even if such aggregation is limited to the choir present. Hip hop, classical ballet, Jimi Hendrix's guitar and the singing of African celebrations meet Chinese ancestry. There are no more barriers, there are only bodies that move in their own way, in their own time, they just move. Moving is good, it is synonymous with progress.

The best thing is to realize that there is no manichaeism in Ryan Coogler's portrait: Remmick seems to propose the same thing, but in a different way. Instead of liberating the soul and inviting us to fraternize with who we were and who we will be, Remmick advocates a form of assimilation, and all assimilation requires us to give up who we are. He sings a folk song, which is equally hypnotic as the one sung in the bar, and all the undead bodies dance and sing the same harmony as Remmick. It is the loss of the self in order to be accepted among those who are different, in order to have the power to defeat racial hatred. Sinners uses its ambitious narrative to discuss whether we want to renounce who we are in favor of acceptance through assimilation, which is always false, as it devours and destroys the soul. Its vampire metaphor (with all the paraphernalia of wooden stakes, holy water, garlic, etc.) questions the African-American community, but it could be any minority group, whether it is worth accepting the threat of colonizers who promote hatred and violence. I can imagine, despite my limited view, the film as a dialogue with the black woman who straightens her curly hair to be accepted within the white aesthetic standard, or the man who refuses to wear traditional clothing, or the artist who photographs black skin as if it had the same properties as white skin, of absorption, reflexivity, and beauty.

In a conformist society, singing the blues and dancing to the rhythm of the ancestors is a sin. And I love the fact that Coogler recognizes the apathy of the small group of survivors, who intend to save themselves by waiting for the sunrise, as if it were a promise of a better tomorrow, not just the anticipation of the night, in which hatred and violence promise to repeat themselves. The way to face evil is to fight it, not to retreat into the bars and ghettos where society pushes these marginalized groups, and the one who invites evil is the Chinese Grace (Li Jun Li), who is the one who ‘directs’ the camera movement at specific moments. Unintentionally, Sinners dialogues with the present in the Chinese retaliation against the American imperialist acts. It is a coincidence, yes, but it works in the narrative. I could even complain about the confrontation, for its brevity and its lack of rhythm - because there seems to be a lot of more humans than vampires, have the ancestors returned to help? - but I would be wasting words. My role as a critic is not to point out ‘rights’ and ‘wrongs’, but to provide my reader with the experience through my eyes.

The climax only bothered my rational self, because my soul wanted to learn the dance steps and respect the ever-oscillating rhythm of the blues, and then fight alongside those threatened with losing the roots that unite them to their ancestry and spirituality. The soul of Sinners is beautiful, and the best films are imperfect, because the more authentic the art, the greater the risk of frustrating formulas and conventions in favor of the present. Ryan Coogler, you've thrown me off balance, but I'll give my final words to Wunmi Mosaku, whose performance I was already enchanted by in the xenophobic horror film What's Left Behind (2020) and whom I've now fallen in love with it completely, and Delroy Lindo, who is the one who best portrays, with his maturity and sensitivity, the traumatic themes of Sinners, while his joviality and mischievous sense of humor reinforce the typical elements of the genre, since, in the end, making a genre film is a blink of an eye to the viewer.

Or a supernatural guitar riff.

Eu amei esse obra! Não poderia concordar mais com você quando diz que os melhores filmes são imperfeitos. Ele realmente tem problemas, mas pelo contexto total da obra ser tão bom, acaba que passa desapercebido.

Um filme que me arrepiou! Autêntico e ousado. A cena do Sammie cantando e os mundos se unindo é pura arte e realidade ao mesmo tempo. Me arrepiei inteira e fiquei hipnotizada.